A university-visiting trip to Scotland afforded me the opportunity to take a quick look at the Scottish political landscape. Although my view will be dismissed as that of an ignorant Sassenach, Scottish politics seems to be only just recovering from a major car crash and has been dumped in A&E (for far too many hours) before returning to the scene of the accident to argue about who left the engine running. There seem to have been several lengthy dramas all unravelling at the same time:

- The SNP are trying to shrug off a long-running finance inquiry while holding on to its core.

- Scottish Labour are attempting to turn Westminster gains into Holyrood momentum and finding the conversion rate disappointingly low

- The Conservatives (“who?”) have been reduced to a rump and are trying to find a voice.

- Reform UK are suddenly visible, where five years ago that would have been unthinkable.

While there seems to be a palpable sense of “drift” a hard stop is now all too clearly signposted by next May’s Holyrood election, which will not simply redistribute seats, but is likely to rewrite narratives about competence, Unionism and the plausibility of Scottish independence as a practical objective.

Runners & Riders

The SNP – after the painful years at the end of the Sturgeon era through the investigation of the SNP leadership’s financial corruption (Operation Branchform) and Humza Yousaf’s thankfully brief leadership, John Swinney has “steadied the ship” and placed himself as the practical centre of the nationalist project. He is not a showman, or a reformer who wins column inches, but he has the advantage of incumbency and the remains of an effective electoral machine across Scottish communities. The SNPs reputation has been significantly dented by the long running police probe into the misuse of its campaign funds, which remains a structural problem for the SNP’s ethical standing, even when prosecutions have been slow to land thus far.

Swinney’s task is to try to translate incumbency into a case that independence remains a practical route to better public services, rather than merely an identity project. On current polling the SNP retains a plurality of Scottish votes and is likely to remain the largest party at Holyrood, even if a single party majority is unlikely. The SNP paradox remains: electoral durability despite reputational damage. The SNP has become the serial fraudster who still tries to reassure its voters that it really will now try to do a better job. No-one’s happy with it, but there you go…

Scottish Labour – Anas Sarwar’s party carries, awkwardly, two sets of expectations. In Westminster Labour delivered a huge victory in 2024 with a story of recovery, but Scottish Labour’s poll numbers for Holyrood have been distinctly less flattering. Sarwar is playing a classic Opposition gambit: focusing on public services, housing and the everyday grievances that matter to voters.

The Hamilton, Larkhall and Stonehouse by-election in June seemed to offer Labour some hope: a Labour win that some read as evidence Sarwar could replicate Westminster success north of the border. In truth the by-election was more of a corrective than a conversion: Labour won, but on a vote share that reflected local factors and the fragmentation of the Unionist vote, rather than a wholesale shift in hearts and minds. If Labour want to displace the SNP they need to show sustained recovery across several demographic groups and regions, not just win the odd by-election.

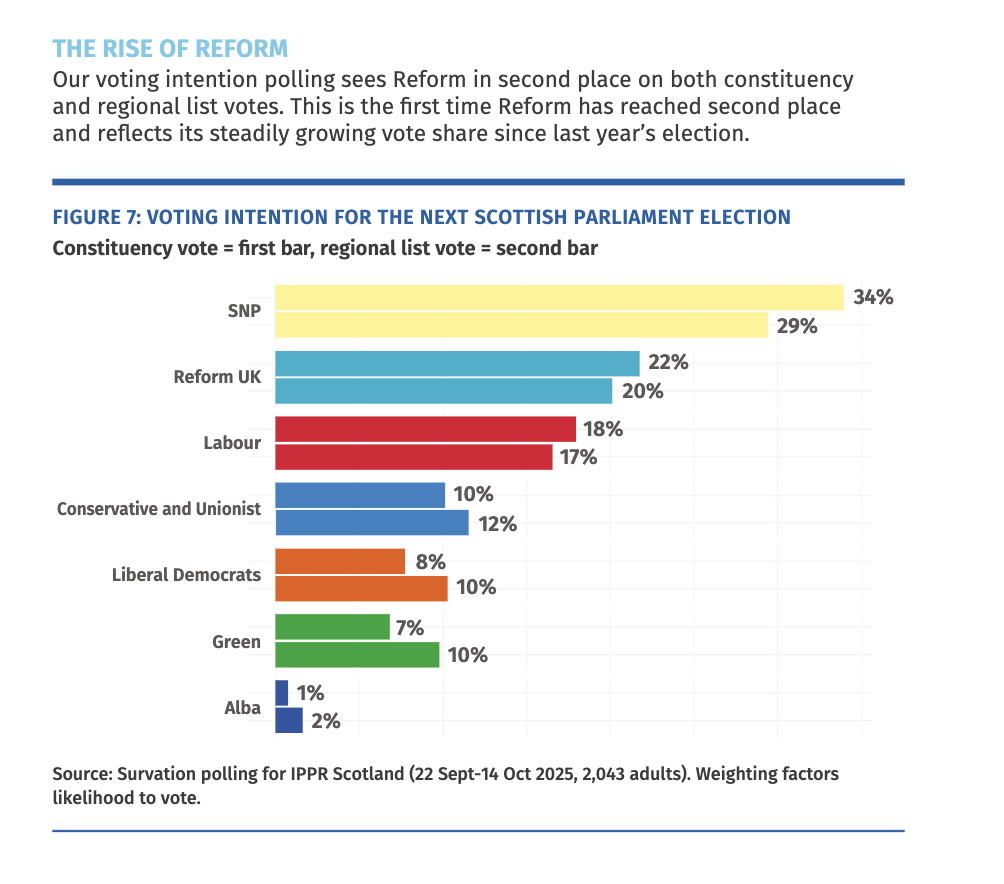

Reform UK – this autumn has seen the appearance of Reform as a force in Scotland. IPPR Scotland polling conducted in October placed Reform second on both constituency and list votes in its fieldwork and other projections have produced similarly surprising scenarios in which Reform could finish well ahead of Labour in parts of Scotland.

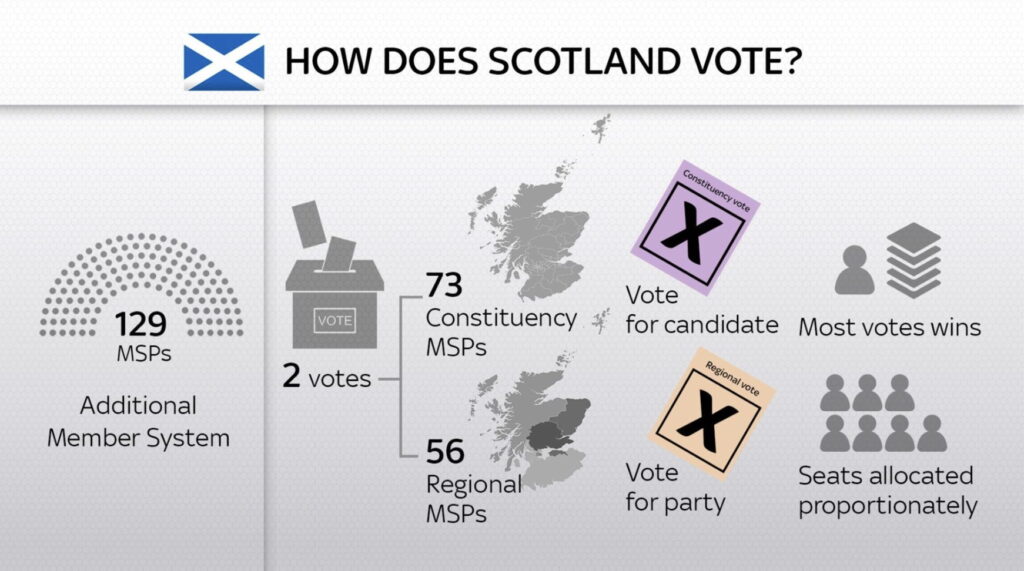

This sort of result would not be merely tactical, but would threaten to redraft the arithmetic of Unionism. Under the new Additional Member System rules, a strong Reform showing on the regional list would cannibalise Labour and Conservative list votes and could paradoxically increase the chance of a pro independence majority if the nationalist parties hold decent constituency hauls.

That dynamic, alarming though it is for Unionists, is not the same as translating into a parliamentary machine for Reform: organisation, candidate quality, and vote distribution all matter and we have seen surges in polling that do not always translate in to seats at subsequent elections. Nevertheless, the potential for Reform to be a spoiler, or a force of realignment, is now non-trivial.

Conservatives – once the last remaining effective Unionist pole, the Scottish Conservatives have been hollowed out by a combination of poor national performance, leadership churn and the simple arithmetic of a party whose Westminster fortunes and policy choices (Brexit, austerity) remain toxic to many Scottish voters. Russell Findlay’s leadership has stabilised the party in process terms, but the question is whether it can reclaim enough ground from Reform and Labour to avoid being squeezed into irrelevance.

The Tories are now fighting for clarity of identity as much as for votes.

The Polling Landscape

A pattern seems to have emerged across the summer and into the autumn:

– SNP remain ahead in most multi-party polls as Labour are flattered by Westminster position, but struggle to convert that into Holyrood momentum

– Reform showing as a (strong!) wild card

– Conservatives languish, becalmed at very low tide.

Electoral Calculus’ MRP models, which have been optimistic about Reform in England, have also shown scenarios where Reform takes a surprisingly large share in Scotland. The caveat is familiar: polling in Scotland has pockets of volatility, different pollsters show different pictures and translating list support into seats under the new AMS (“system”) is tricky. AMS looks to me to be an overly-complicated way of distancing politicians (even further) from contact with reality, or accountability. It should be canned. Still, the headline for Unionists is stark: fragmentation risks handing a comfortable plurality to the SNP.

By-elections and local outcomes

The Hamilton by-election in June was the most concrete political event of the year thus far. Labour’s Davy Russell took the seat with 31.6%, the SNP trailed on 29.4%, while Reform polled an extraordinary 26.1%. The headline was “Labour wins”, but the story was really: “fragmentation.” Reform established itself as a credible third force and the Conservatives were relegated to “also rans.”

Journalists and academics called Hamilton a test of whether Reform’s English appeal could translate north and: it did! But by-elections have idiosyncrasies. Low turnout, local controversies and the presence of high profile campaigners can move numbers in ways that make extrapolation dangerous. Nevertheless, Hamilton was a shot across the bows for Unionists and a reminder that the centre ground is no longer a comfortable space to defend.

Scandals and state capacity: why competence matters

A theme beneath several recent Scottish headlines has been: governance failures, procurement mistakes and the long tail of investigations. This has created a cumulative impression of dysfunction that feeds voter frustration. Two emblematic episodes stand out:

- Operation Branchform. The long running Police investigation into SNP fundraising damaged trust, consumed resources and left a residue of excoriating headlines that the SNP still has to manage. The inquiry’s proceedings, arrests and prosecutions and the slow pace of resolution have been a political gift to opponents who cast the SNP as economically and ethically reckless. Even after investigations did not produce charges against senior figures (yet!), the reputational hit has been real.

- Ferry and energy procurement scandals The long running Ferguson Marine and CalMac fiasco, the delayed ferries, the swelling costs and the contested procurement choices have felt like an avoidable catalogue of managerial failure. That sense of “how did this happen” is compounded by recent reporting that suggests Scotland’s 2021 ScotWind auction may have left taxpayers badly short- changed, with critics calling for a speedy audit. These seemingly endless stories make Scots ask whether their State can manage big projects and whether the Scottish political class understands money, or markets. Politically, these questions reverberate beyond particular ministries, reframing the “Broken Britain” story in to a potent Scottish context that drives voters toward parties promising simpler, sterner solutions.

May 2026

It is tempting to sketch some simple scenarios: SNP majority, Unionist coalition, or chaotic hung parliament. The truth is more nuanced.

1. If Reform sustains a double-digit share on regional lists they will win seats and punish Labour and Conservative list hopes. That fragmentation helps nationalist parties retain influence even if their constituency totals fall slightly.

2. If Labour rebuilds across its traditional urban heartlands and converts its Westminster brand into a clear, homegrown offer on schools and the NHS, it can reduce the SNP’s bargaining power and position Sarwar for a credible contest. Hamilton suggested Labour can still win in Scotland, but it was not yet proof of conversion on the scale Labour would need.

3. If the SNP can demonstrate competence and keep independence talk framed as practical policy rather than constitutional grievance, it can blunt unionist gains. The party’s better local organisation remains an advantage.

A more complicated scenario for Holyrood’26 might be: SNP remains the largest party, but the overall composition of the chamber will depend heavily on the size of Reform’s ”list” vote and whether Labour can rebuild in the constituencies. This leaves open very Scottish possibilities: either a minority SNP government working with allies, or a chamber where ad hoc majorities form on particular bills, rather than a durable coalition.

This outcome is then likely to shape the constitutional conversation (known otherwise as “despair”) as much as the domestic policy agenda. Cue lots of depressed Scottish introspection. Aye, aye, mebbe, it’s nah ideal (apologies.)

What to watch for

Practical signals to monitor what may change the narrative before election day include:

- whether Survation style polls hold their ground across other pollsters, or whether the Reform surge is a transient mood

- court developments from Operation Branchform and the extent to which the SNP can distance itself from reputational damage

- Audit or Parliamentary investigations into ScotWind and high-profile procurement stories which will feed the “competency” argument or lack thereof

- Labour’s capacity to show sustained, localised gains rather than isolated by-election wins

- Reform’s ability to convert a strong list showing under the new and intentionally Byzantine and confusing AMS rules into seat wins, or fades into voting protest.

The Scottish political mood

Scottish politics now revolves around competence, identity and trust. Independence remains, just, a “live” project, but for many voters the immediate questions are school places, ambulance waiting times, ferry timetables and energy bills. Parties that answer those questions will succeed.

This in turn, accentuates tangible delivery over rhetoric: a paradox for the SNP which tries to keep independence alive as a while trying to deliver services that it has failed to do under its watch. It is also a challenge for Unionists, who must offer a credible alternative on governance and not merely argue against constitutional change. Reform’s surge, if it persists, will be a potent reminder that political realignments can come fast when voters feel they have been failed. They do.

Bottom line

Holyrood ‘26 will not only test independence sentiment: it will pass judgement on the SNP’s competence, Labour’s attempt to translate Westminster electoral success into Scottish votes, whether the Conservatives can halt their slide and, most intriguingly, whether Reform is a fleeting protest, or a real threat in Scotland. Reform is now the unanswerable wild card. Expect volatility, surprises and a legislature that may be more dependent on Byzantine and lengthy negotiations than ever before.

Conclusion

“Nay laddie, it’s all shite.”

Leave a Reply