MERITOCRACY VS POSITIVE DISCRIMINATION – The tension between meritocracy and positive discrimination has shaped numerous debates in British politics since the mid-20th century, focusing on how to ensure fair access and optimal outcomes in education, employment and the conduct of public offices.

Recent policy shifts, such as the government’s proposal to reserve civil service internships for candidates from “working-class backgrounds” announced (suspicious timing for political cynics) during Parliamentary Recess, together with the earlier decisions to remove private schools’ VAT exemption and revise inheritance tax for farming estates suggest a decisive tilt towards “positive” discrimination. (Some might call it “class prejudice.”)

These changes raise fundamental questions about fairness, social mobility and the limits of state intervention in addressing historical inequality. The probability of the Law of Unintended Consequences now looms on the immediate horizon.

The Ideal of Fair Competition

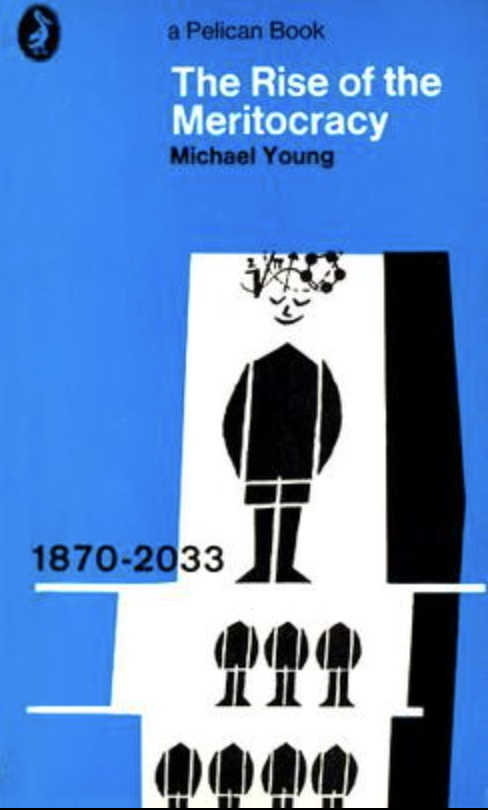

The concept of meritocracy was popularised in British discourse by Michael Young’s satirical 1958 book “The Rise of the Meritocracy”, in which he envisioned a dystopian society stratified entirely by measured ability¹. Ironically, although intended as a joke by no less a figure than the founder of the Open University and the Consumers Association himself, the term was embraced as a democratic ideal. Irony is so often too delicate a flower to grow as the writer intends.

Meritocracy, in its modern and political usage therefore, is advanced as an antidote to both aristocratic privilege and bureaucratic patronage. Politicians from Margaret Thatcher to Tony Blair and now including Pat McFadden (who he? ed), have invoked “meritocracy” in order to justify policies promoting educational excellence, open competition and professional accountability².

However, this latest piece of the class war initiative comes against a backdrop of the UK civil service having long been proud of its merit-based recruitment and promotion systems, underpinned by anonymous applications, rigorous testing and competitive interviews³.

Critics of “McFaddenism” (a Scottish attempt to follow political fads, eh? ed) argue that pure meritocracy is an unachievable objective and that the tokenism of the move to restrict access to class-defined candidates may be aimed at satisfying class antagonism, rather than achieving any real improvement in outcomes. Those from wealthier backgrounds will continue to benefit from better schooling, networks and cultural capital, factors that are invisible in CVs, or at interviews⁴. As a result, what appears to be “fairer” competition may simply entrench existing privileges and lead to them being more effectively hidden from recruitment processes.

Quotas: Levelling the Playing Field

Quota systems seek to correct embedded inequities through affirmative action, or positive discrimination, deliberately increasing the representation of previously “minority” groups. In the UK, while formal quotas are rare, “targets” or “ring-fencing” measures are more common, particularly in public-sector recruitment and university access schemes⁵.

The latest government announcement that civil service internships will be “reserved” for applicants who can demonstrate that their parents had “working-class” jobs seems to be an extreme form of ring-fencing⁶. According to ministers, the aim is to tackle the persistent over-representation of privately educated recruits in Whitehall, despite long-running efforts to diversify recruitment⁷. (Personally, I have to say that I do not discern a scrum, or even any less class-ridden sporting analogy, of private schoolers rushing to join the civil service – just saying!)

This move follows on from other redistributive measures: the removal of VAT exemptions for private schools⁸ and the ending of inheritance tax relief for family farms above £3 million in value⁹, both of which affect the affluent and have been framed as correcting unjustified privileges. However, while causing individual hardships and disruptions, these measures will have had no discernible impact on educational fairness or inter-generational inheritance trends (other than a little flurry of additional spending on the lawyers and accountants who can re-arrange those farm holdings in a nice little trust – another irony!) If in doubt, put it in trust is a motto for the ages.

“Fairness Through Structural Correction”

Meanwhile, supporters of these reforms argue that true meritocracy requires interventions. If working-class students are systematically excluded from elite pathways then merely judging everyone by the same criteria is likely to preserve existing inequalities¹⁰.

From this perspective, quota-style interventions are not anti-meritocratic, but pro-opportunity. By ensuring that those from disadvantaged backgrounds have access to opportunities that were previously monopolised by the privileged such policies aim to create a fairer and more socially mobile society¹¹.

In addition, quota advocates point out that diversity in public institutions like the civil service is a democratic good. A Whitehall composed mostly of Oxbridge graduates from the South-East cannot effectively understand the needs of the whole country.¹² This seems to underestimate the ability of Oxbridge graduates to understand the experiences of “other” populations – look at those marine biologists go, understanding the social behaviour of orcas in the Straits of Gibraltar! Whatever next, the microcosm of Sunderland suburbs falls prey to the prejudices of Oxbridge sociologists???

Tokenism and Reverse Discrimination

These “meritocratic” policies themselves raise serious concerns about fairness, efficacy and public perception. Reserving internships based on parental occupation very obviously replaces one kind of discrimination with another. Talented students from non-working-class backgrounds may feel excluded on the basis of family history, an attribute entirely beyond their own control.

These policies also may be more about “optics” than substance. A “working-class” intern may still face exclusionary cultures, or lack the mentorship needed to thrive. Worse, they could be painted as “diversity hires,” undermining their own credibility13 and potentially bringing themselves and the re-engineered recruitment system into ridicule.

The invasion of personal privacy, requiring young people to “prove” the class background of their parents, is also obviously problematic from both privacy and civil liberties perspectives. It raises complex definitional issues which have evaded robust and precise definitions within the ever-nuanced complexities of British social definitions for, literally, centuries. What exactly constitutes “working class” in the 2020s? Does the child of a successful self-employed plumber still qualify, while the child of two state school teachers can never hope to escape their middle-class label despite basic poverty? This is so obviously bogus it makes one wonder how it got through the normally rigorous assessment that (admittedly “elite”) civil servants test ministerial “brainwaves” with.

The Politics Behind the Policy

The recent shift towards class-based redistribution reflects a deeper recalibration of UK political priorities, particularly on the centre-left. Labour under Keir Starmer has emphasised breaking down barriers to opportunity while appealing to traditional working-class voters disillusioned with the status quo. Meanwhile, parts of the Conservative Party have also embraced elements of “levelling up,” though often with less emphasis on redistributive taxation14 and with an unusual degree of incompetence.

This convergence has made class, rather than race or gender, the central axis of current “positive action” policies. Class-based measures are generally less legally controversial and more broadly supported by the public than identity-based quotas. However, they also risk alienating aspirational middle-class voters, especially those who have invested heavily in private education, or those who come from families with modest, but non-working-class roots.

Comparative Perspectives and Legal Limits

It is worth noting that UK law prohibits most forms of “positive discrimination” under Harriet Harman’s Equality Act, 2010. While employers can take “positive action” to improve access or outreach to underrepresented groups, they cannot hire or promote someone solely based on protected characteristics except in very narrowly defined circumstances.

Class, however, is not a protected characteristic, which allows more legal “flexibility.” Nevertheless, this creates a grey area: whether ring-fenced internships violate equal treatment laws may depend on how the scheme is administered. The risk of legal challenge remains, particularly from excluded applicants.

Striking the Balance:

Towards a More Nuanced Approach

The central challenge is balancing the appeal of meritocracy with the pragmatic need for redress. Policymakers should at least try to avoid both extremes: the complacency of assuming that a level playing field already exists, but also the overreach of trying to engineer outcomes at the cost of individual fairness.

A better path could lie in universal measures that disproportionately help the disadvantaged without explicitly excluding others. For example:

- Expanding internship availability and ensuring all are paid, so that lower-income students can afford to participate.

- Improving school and university outreach, so that civil service careers are demystified for those outside traditional pipelines.

- Enhancing recruitment criteria and processes, such as anonymised applications, to reduce unconscious bias.

These strategies uphold the principle of merit while acknowledging the reality of unequal starting points. They aim not to replace meritocracy, but to make it real.

Conclusion

The debate over meritocracy and quotas in British politics is not new, but it is intensifying. As the UK grapples with the legacy of entrenched inequality and public distrust in elite institutions, policymakers face difficult choices. Efforts to open up the civil service and challenge privilege risk unintended consequences if not carefully designed.

There is ample evidence of a growing crisis of UK competence over the last 20 years, just as “elite” privileges have been questioned and reduced. The real challenge is how to preserve leadership capabilities while engineering wider and unprivileged access to opportunities. In the current middle-ground of meritocracy, the UK has incorporated the worst of both worlds: decrying all forms of competent leadership as “elitist” while failing to build truly equal-opportunity excellence. This failure is most starkly epitomised in the form of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, who is clearly not sufficiently competent to grapple with her complicated brief, but who has been thrust in to that rôle because of a preferential regard for those unlikely to have been identified as capable leaders. One has to wonder how many “elite” Treasury mandarins are working overtime to prop up their manifestly struggling non-elite “leader”?

The restriction of civil service internships to the offspring of working-class parents is absurd, counter-productive and addle-brained. Encouraging interest from non-traditional candidates should (like Oxbridge entrance) be pursued with outreach and targeted support, not by the exclusion of potentially excellent candidates.

Ultimately, a society that prizes both fairness and excellence must look beyond binary solutions. Merit must remain the objective, but this should involve ensuring that everyone has a genuine chance to compete and the promotion of those who demonstrate capability, further potential and leadership qualities.

Footnotes

1. Michael Young, “The Rise of the Meritocracy” (London: Thames & Hudson, 1958)

2. Stephen J. Ball, “Education, Justice and Democracy: The Struggle over Ignorance and Opportunity” from Anthony Montgomery & Ian Kehoe (eds,) “Reimagining the Purpose of Schools and Educational Organisations.” (London: Springer, 2016)

3. Cabinet Office, “Civil Service Fast Stream Diversity Statistics”, 2022 & 2023

4. Daniel Markovits, “The Meritocracy Trap – How America’s Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class and Devours the Elite” (New York: Penguin, 2019)

5. Sally Tomlinson, “Education and Race from Empire to Brexit” (Bristol: Policy Press, 2019)

6. UK Government Press Release, “New Civil Service Internship Scheme to Prioritise Working-Class Candidates”, 1st August 2025

7. Social Mobility Commission, “State of the Nation Report 2023” (London: HM Government, 2023)

8. HM Treasury, “Spring Budget 2024” (London: HMSO, 2024), Section 6

9. DEFRA, “Changes to Agricultural Property Relief”, Policy Note, January 2025

10. Joseph Fishkin, “Bottlenecks: A New Theory of Equal Opportunity” (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016)

11. Robert D. Putnam, “Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis” (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015), adapted for UK context in BBC Radio 4, “How to Crack the Class Ceiling”, 2022 but sadly no longer available on iPlayer for inscrutable reasons

12. Patrick Diamond, “The Civil Service and Social Mobility” (London: Policy Network, 2020).

13. David Goodhart, “Head, Hand, Heart: The Struggle for Dignity and Status in the 21st Century” (London: Allen Lane, 2020)

14. “Levelling Up White Paper” (London: HM Government, 2022).

Leave a Reply