SOFT LAUNCH It is traditional for governments to slip out news of their most depressing failures in the dying moments of Parliamentary “term” in the hope that MPs and journos alike are keener to hit the fleshpots of the Mediterranean or more exotic holiday destinations than to pursue the latest delay to HS2, or estimated cost increasea for Sizewell C, or the inability of anyone to convince Junior Doctors to accept basic maths in order to avert their continually-threatened strike action. However, bar these perennial favourites, other news shockers seemed thin on the ground this week. In this environment we turn to the dryest of dry topics: the UK’s dire fiscal position months (count them!) before the Chancellor has to find some new bogeyman to blame for having no money for anything at all.

Time to be real

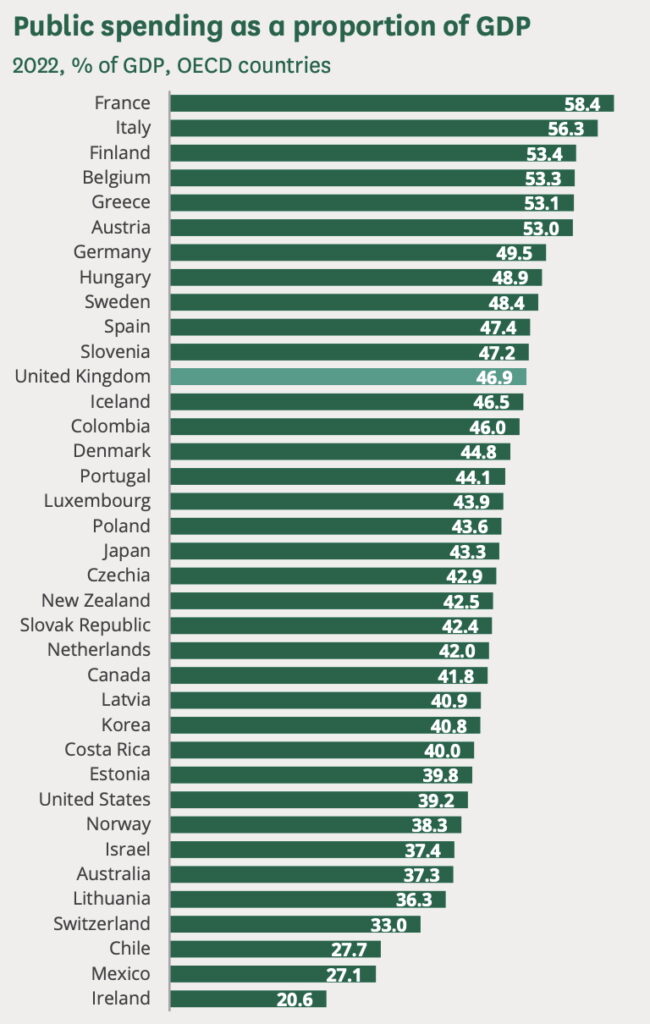

UK “normal” public spending has represented around 45% of GDP in the 2020s and is expected to hover at 46-47% in 2025/6. Although there is a general air of crisis surrounding UK public expenditure, this level actually puts the UK in the central band of OECD nations’ public spending (12th out of 27 OECD nations.)

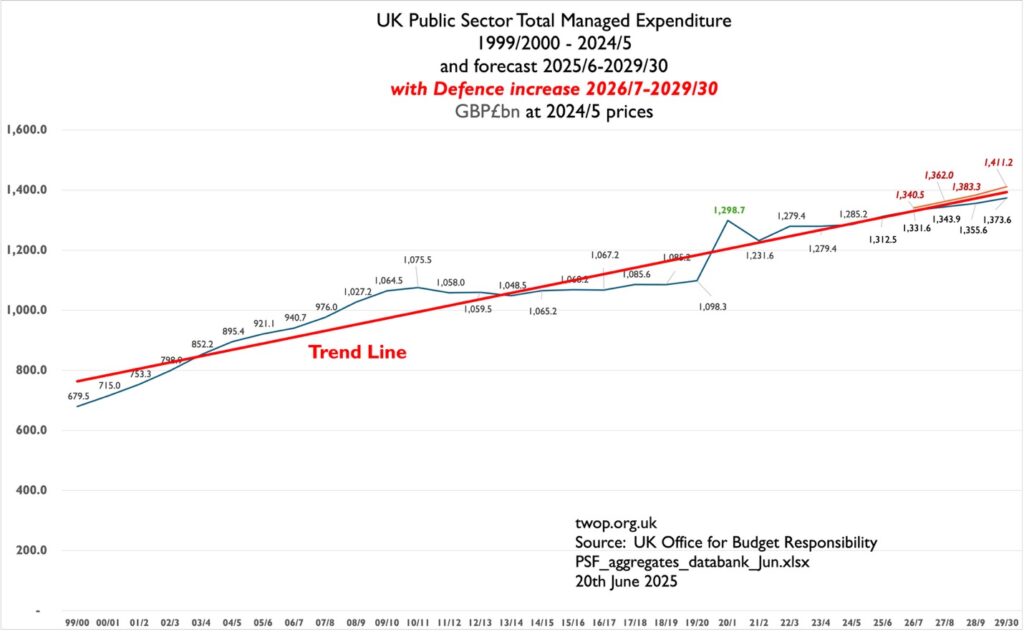

Nevertheless, the trend in UK public spending has been moving relentlessly higher through the first quarter of this century, even without the COVID “spike” of 2020/1. This chart shows the inexorable rise in UK public spending in real terms (2024 prices) with the latest projected increase in defence spending NATO members committed to making by 2035 shown through the addition of an extra cumulative 0.3% of GDP to be spent in each year from 2026/7.

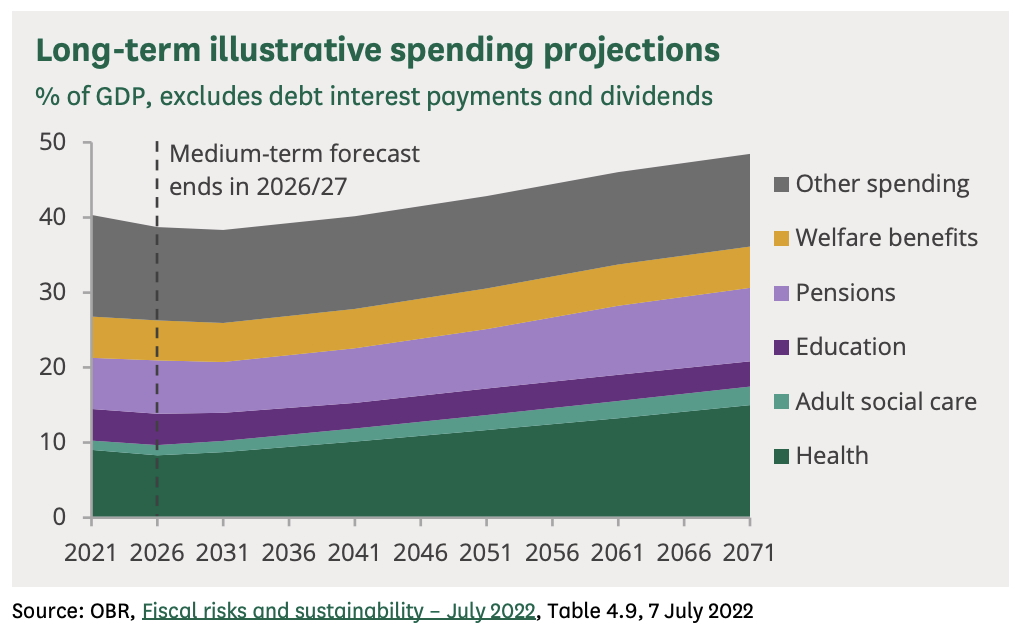

Before the commitment to increase defence spending, recent OBR forecasts projected a small dip in total public spending as a proportion of GDP between 2026 and 2031 before spending growth returned to long-term trend growth between 2031 and 2071.

This analysis suggests that over the next 50 years, total UK public spending would rise, reaching around 48% of GDP by 2071/2.

However, in June 2025, in response to US pressure, NATO members including the UK committed to increase their defence spending to 5.0% of their GDPs by 2035. The UK has only recently committed to increase defence spending from 2.3% to 2.5% of GDP so, if the further “Trump” increase is to be taken seriously, a further 2.5% of UK GDP must be presumed to be dedicated to defence by 2035 (although politically it looks very much as though most NATO governments were crossing their fingers behind their backs and actually now hope to revise this commitment downwards in 2029, while creatively accounting for bridge-building and cyber-security enhancement as “defence” until that time.)

So, for the time being, it would be best to account for an 0.3% GDP increase in public expenditure every year through to 2035 to reflect this commitment. This increase would bring forecast UK public spending to 50.5% in 2071/2, on the (reasonably safe) assumption that the 2.5% of GDP increase in defence spending can not be funded by those ever-ephemeral “savings” in other public expenditure areas.

Health spending would be the largest contributor to the underlying spending increase. This is partly because the aging UK population will need greater and more expensive health services as new treatments and therapies are likely to become more expensive as new health technologies are invented, but also because the prevalence of chronic conditions such as diabetes and obesity has been increasing in the UK in recent years.

Pensions would be the second largest contributor to UK spending growth 2031-‘71, because of the changing age profile of the population.

However, the ageing population could also result in some proportional spending decreases as fewer children could allow lower proportional spending on education, except that these sort of projected reductions often turn out to be illusory as budget holders determinedly defend their spending areas.

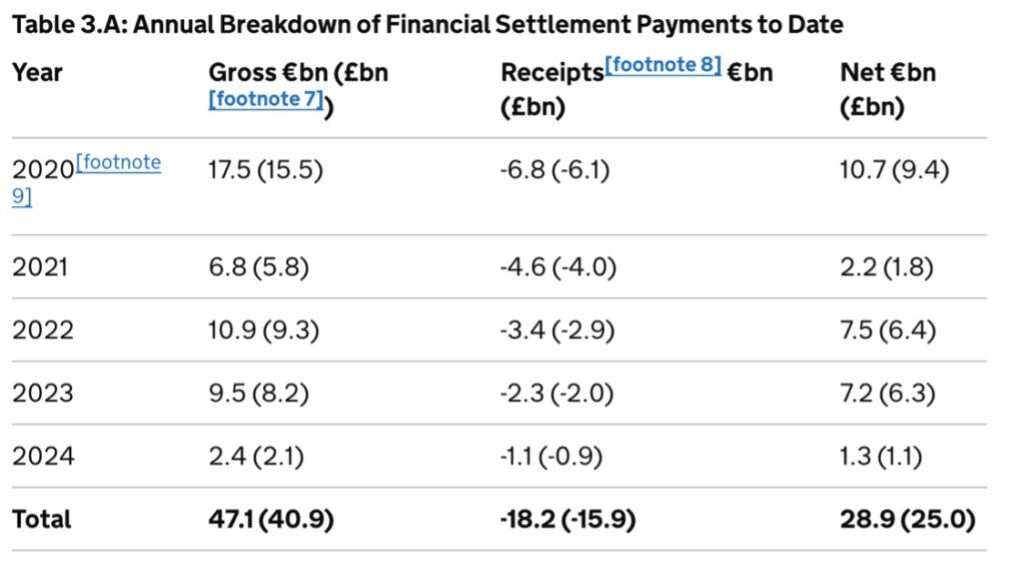

Another probable reduction in UK spending should crystallise in the politically charged area of the UK’s net contribution to the EU. These payments have already reduced since the 2020 Withdrawal Agreement and in 2024/5 the net residual payment to the EU had fallen from ~£7.2bn pa in 2021/2 and 2022/3 to “only” £1.3bn in 2024/5.

This reduction in EU net payments must be set against potential reductions in UK income now likely to arise from Trump-driven changes in the terms of international trade, illogical though they may be and this is in keeping with the most significant theme of UK public spending reform: projected “savings” always prove illusory.

The Starmer government has attempted to reduce welfare and education spending at the margins by:

- reforming pensioners’ winter fuel payments (£2bn pa target savings)

- altering “PIP” Personal Independence Payment regime (£5bn pa target savings)

- changing “SEND” Special Educational Needs & Disabilities (no savings)

but these attempts have demonstrated how difficult it is for governments of any hue to clawback spending from recipients who have become used to various forms of support, even with substantial and recent electoral majorities. It will be interesting to see if the two-child cap on child benefit payments introduced by the Tories in 2017 and retained by Reeves against significant Labour backbench hostility makes it through to the 2025 Budget in October or November.

The target for UK governments of any stripe must be to reduce public spending as a proportion of national income over the long term so that in “Competitive Advantage of Nations” terms that Michael Porter would recognise, while keeping the nation safe and economically prosperous. A reduction of 5.0% in UK public spending as a proportion of GDP would be sufficient to move the UK from 12th position in the OECD spending table, vying with Slovenia and Iceland to 24th and competing with the Netherlands and Canada for “lower spending” status. This type of target can be reached either by reducing costs, or increasing income and growth, or a combination of these. I will turn to the seemingly eternal question of the Great British Growth Stagnation in a subsequent article, but on the cost side of this equation the only area that has sufficient scale to offer the prospect of this scale of change is – drumroll…

Pensions

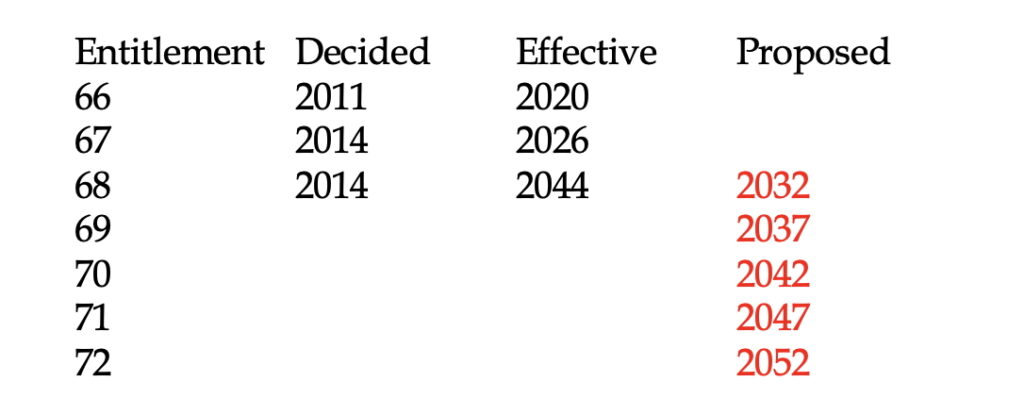

Long-term savings in UK state pension entitlement could be achieved by accelerating the increase in the age of entitlement. Currently the increase to 67 is being introduced from 2026, while the move to 68 is being accelerated from 2044 to 2032 and needs to be increased to 72 by 2052 just to keep in line with life expectancy trends. An immediate end to the “pensions triple lock” would pave the way for more substantial savings by removing the link in increase in state pension payments to earnings and instead reverting to the link to inflation. These two changes should also be implemented alongside measured to encourage private pension provision from in-employment savings and reduce the overall cost of state pension provision dramatically over the next 50 years.

History of UK State Pension Age Entitlement

Universal pensions were introduced in the UK as a non-contributory safety net for the elderly poor with little other income by the Old Age Pensions Act, 1908 when life expectancy at birth was just 45 for men and 49 for women. On introduction in 1910 it was calculated that less than 2% of the UK population would qualify for pension support. By 2021 life expectancy at birth had increased to 79 for men and 83 for women and just over 20% of the total UK population qualified for state pension payments. ONS projections suggest that on current population and age expectancy trends, the proportion of people of pensionable age (at current entitlement ages) will reach 27% of the total population by 2072.

After the equalisation of pension entitlement ages between men and women in 2010 and the revision of the schedule for the increases to entitlement ages to 66 in 2020, 67 in 2026 and 68 in 2044, the 2017 Cridland Review established a benchmark for individuals’ expectations of spending 32% of their adult lives in receipt of state pension and recommended accelerating the increase of entitlement age to 68 by 2032 and subsequently by one further year per decade to maintain this criterion for intergenerational fairness.

The programme of increasing the age of pension entitlement now needs to be accelerated so that entitlement is increased to 72 over the next 25 years.

On introduction in 1908 the conception of the state pension was to make a non-contributory safety net for the elderly poor and therefore set at a pension payment of only £13pa for those aged over 70 in receipt of less than £21pa income (at a time when average wages for working men would have ranged from £150pa to £200pa.)

This original state pension conception was fundamentally altered to a contributory basis by the 1946 Pensions Act which also introduced an earlier entitlement age (60 for women and 65 for men), moving from a late-age safety net for the elderly poor to a wider minimum income guarantee for a more broadly-defined portion of the older population.

From the introduction of contributory pensions in 1946 the pension payments had been linked to the annual rise in average earnings, but Margaret Thatcher’s government ended the earnings link in 1980 and instead uprated pension payments annually in line with the RPI measure of retail inflation. This decision reduced the comparative value of state pensions as wage growth outpaced inflation, but this saving was reversed by Tony Blair’s government in 1997 when the earnings link was restored.

In search of the “grey vote” the Conservatives went further during the David Cameron’s Coalition Government in 2010 and introduced a “triple-lock” guaranteeing annual pension increases equal to the higher of inflation, earnings, or 2.5%pa. This multi-point uprating has seen the value of the state pension increase from £5,000pa in 2010 to £12,000 in 2025, an increase of 240%, over a time period in which inflation (as measured by CPI) has increased prices by 50%, representing a truly enormous uprating of pensioners’ income. A single person’s pension payment was increased to £230/week (£11,973pa) from April 2025.

State pension provision cost £111bn in 2022/3 and £124.0bn in 2023/4, which represented just under half of total government benefit expenditure.

TIME FOR MAJOR PENSIONS CHANGE

The continuing growth of the proportion of the UK population living to and beyond pension age over the next 50 years together with continuing the annual uprating of pension payments in line with earnings, will make the costs of the state pension entitlement unaffordable by 2070. However, the planning horizon for pensions is intrinsically a very lengthy one and beyond the planning cycle of any government.

These structural changes to the UK state pension regime could produce significant changes in the UK’s long-term public spending as a proportion of GDP:

| Policy | Spending % of GDP |

| Bring forward increase to 68 to 2032 and then continuing this increase in single year increments to reach 72 by the 2050s | 4.0% |

| Breaking pensions triple lock and make annual uprating based on CPI inflation measure immediately | 2.5% |

| Privatise pension provision for all UK citizens currently aged under 45 and alter tax structure to further favour private pension-derived income from 2050 | -1.5% |

| FUTURE PUBLIC SPENDING REDUCTION | 5.0% |

It may be seen as rather cynical for a relatively young person to focus on pensions reform as the route to reducing the UK’s public spending, but by focusing on the longer-term elements of pension entitlement and the far-distant repercussions of the uprating mechanism within a context of significant encouragement towards private and “individualised” provision under the banner of “personal choice”, would allow the targeting of one of the few policy areas that might deliver significant long-term spending reductions. By focusing these changes on the cohorts likely to attain pension age in more than 20 years’ time these changes also stand some chance of being politically possible, particularly if positioned as part of a long-overdue initiative to address “generational equity.” Just saying…

Leave a Reply